What to build? Timber frame construction example. Source: Timberlyne Homes

What to Build for the Hoosier Homestead?

The land has been purchased and is growing wild in the Hoosier Humidity. Now we need to determine exactly what to build. We began by scouring the various house plan sites. I love a western lodge architectural style with vast facades of windows and a focus on stone and wood cladding and exposed structural members, but I don’t think the style fits in a former soybean field in middle America. K has long been in love with plantation style homes with their symmetrical facades, columned porticos, and pediments, mostly those tall columns, I think. But they carry cultural baggage and are more at home in southern near-coastal regions.

So I began looking at colonial, craftsman, and farmhouse architectural styles. I ultimately gravitated towards a modern farmhouse architectural style. I love the steeper roof pitches, simple roof lines, and the form-follows-function design language. Besides, is there a better match for former farmland than a farmhouse?

No House Plan is Perfect

We searched the plan sites, Pinterest, Instagram, and TikTok for the perfect plan. There were no plans that either of us thought was 100% perfect; what one thought was a good start had some glaring design choices the other could not unsee.

Modern farmhouse design from architecturaldesigns.com

Design the House Ourselves

This will become a major theme of the Hoosier Homestead project. We cannot find someone who will do it our way, so we do it ourselves. Many of the plans I liked placed the garage forward of the front entry, which K could not abide. K’s plans had inefficient layouts; the garage located too far away from where the groceries were put away.

The plans rarely specified 2×6 framing, nor what kind of details they used for water, air, vapor, and thermal control. The cost to buy the plans and then modify them was steep. So I began designing my own plans, starting with a few of the ones we liked and swapping the things we didn’t out for things we did.

Build Parameters

If you have followed the Hoosier Homestead project since its beginning, which was about two posts ago, you already know that we are building a barndominium, a term I rather dislike. Not just because it invokes imagery about retirement communities and shared walls, but also because barndos are really just a visual style, and most people assume it is a pole barn converted into living space. However, a traditionally framed building could have the same appearance.

I have simplified the terminology for brevity, but when determining what to build, there are four or five things you need to establish:

- Your needs and budget (this goes without saying, and is the most difficult part)

- Architectural style (i.e., the visual style: Colonial, Victorian, Craftsman, Cottage, etc.)

- Foundation type (e.g., slab, crawl space, basement)

- Framing method (e.g., heavy-frame, light-frame)

- Material grades (e.g., thicker sheathing, insulation type, cladding, roofing, etc.)

Needs & Budget

We did not think much about the total budget when we purchased the property. Full disclosure, we are in a privileged position. My primary gig is software engineering, and I’ve worked via 100% telecommute since 2014. Additionally, I have flexible hours. This affords me the ability to work from anywhere with even a marginal internet connection and provides windows of opportunity to apply sweat equity during standard work hours (when subcontractors would also be working).

This means I can be on site as the general contractor and manage trades. But I plan to delve deeper than GC’ing and provide as much manual labor with trades as possible. As of writing this article, all the sweat equity I’ve put in has been with planning (e.g., conversations with contractors, drawing plans, paying for and scheduling material); revisit this assumption of on-site opportunity once the real work begins and ask me if it holds up.

Originating Funds

Ultimately, this reduces our budgetary needs. By how much, though? I won’t know until it’s finished, so this build is also a little bit of experimentation. My big investment is my time, which is worth a lot. However, if I meet my goal of saving 30% on the final cost to build, that built-in equity should pay dividends later.

We were also able to dump stocks I built up over a decade of employee purchase plan before the 2025 crash, timed perfectly with its biggest peak, ever (as of this writing). Combined with a small nest egg I hoarded across five years of side hustles and leveraging some equity of our current home, we arrived at our budget. For full disclosure of numbers, be on the look out for our documentation package.

The Ouroboros of Funds & Needs

Much like the serpent eating its tail, or the conundrum of the chicken or the egg, needs drive the budget but the budget determines which needs you can afford. To determine your needs and budget, most people begin with their budget and then prioritize their requirements for a home. This is a very difficult activity because the market pricing on materials and labor is always increasing, and most people are ignorant about what it truly costs to include specific features. Every other decision that needs to be made will be constrained by budget: architectural style, foundation type, framing method, and material grades.

However, if you have elected to attempt some of the work yourself, it becomes easier; all you have to understand is how the feature is built and the materials involved. Then you just price out the materials (using the pro desk or dedicated contractor supply houses, not just retail pricing at the big box store). Otherwise, this step can be long and arduous, since you need to survey contractors to get average ballpark estimates. When I say survey, I mean no less than 3 contractors per trade. And no more than 5, else you are wasting time, and time is money.

When surveying contractors, be sure to do some due diligence on their work. You don’t need to get references, but do some quick Googling to find reviews on Google Maps, Yelp, and Angie’s List. To discover prospective contractors, you can use those sites, but also see if there a dedicated subreddits for those services (or contractors in general) for your region. Searching Facebook (Marketplace, Groups, and Pages), Instagram, LinkedIn, and TikTok for local services can also be informative (after all, we have a presence in those socials).

Spinning Our Wheels

What was required of our new home changed rapidly, and there were a couple of contested topics between K and me. At first, we thought we could just build a small carriage house (a garage with an apartment on the 2nd floor) on the cheap, then we could mastermind and build our ultimate residence at our own pace. After calling a few custom builders, we quickly realized that my small 2-car garage apartment idea would not be cheap. Between $500k and $750k were the ballpark figures thrown at me. In one of the cheapest cost-of-living corridors in the nation!

That was the moment I considered General Contracting the build myself. First, I looked at modular offerings, and the pickings are slim for pre-fabricated 2-story garage apartments. Then I looked at custom manufactured homes. Then at post & beam packages. Then, finally, at pole barns and pre-engineered metal buildings (PEMB). These final class of structures seemed to offer the cheapest and quickest way to an enclosed building ready to finish.

First Requirement Established

Emphasizing the cost and speed to get a weather-tight shell. Not a finished living space. There is a misconception about post-framed barndominiums being cheaper to build; I can assure you that is not a fact. With the price of concrete, a stick-built home over a vented crawlspace is likely the cheapest way to go. But to have a building with very large clear spans (as in no interior load-bearing walls), that can be erected in less than a week for a fraction of a finished home, post-framed homes are hard to beat.

Approaching a build with a clear span building offers a lot of advantages to a particular niche of homeowners. If you do not need to move in immediately, and have time to do much of the work handled by trades, then I think it affords an opportunity to get more building than what you could with standard financing options that require the budget to be originated wholly at once. This was exactly the position we were in. It allows me to keep my Montana home and get much more home out of our Indiana location. I’ll cover the exact framing style we eventually selected below.

Important Questions with Important Answers

When I say the needs or requirements of a home, I’m talking about more than the number of bedrooms and bathrooms, which, for anyone who has lived in a home with up to five ladies, knows these numbers are super critical. But I’m not talking about watch drawers in massive walk-in closets or having a dozen spray heads in the shower, those are luxury items. I am speaking about durability, comfort, and health. Should the home last more than a generation, or is it a toss-away? Do you want to be cozy regardless of the season, or fight with relative humidity? Are you concerned about the health of the occupants or the environment or can wellbeing be damned?

I wish the former options for each of these were always the answer, but unfortunately, that is not the world we live in. But if you are having a home built, you get an opportunity to answer these questions to the best of your ability. For the Hoosier Homestead, we are striving to implement construction details informed by building science to ensure a home that can be enjoyed for generations. It doesn’t always have to cost more, just greater attention to detail and careful execution go a long way.

How Big Do We Build?

K and I had one major point of contention. In our current home, we end up with a lot of clutter. I have a ton of hobbies, and the kiddos have tons of toys. Our eldest is a clothes and shoe hound, and I have yet to see a storage solution that can fit her hoard. It is mostly about not every thing has a dedicated home. We don’t have enough cabinet space to neatly organize all the pots and pans. K’s collection of neat kitchen tools and equipment has to be hauled to storage in the utility closet two flights of stairs away. My board games are stacked atop full bookcases to the ceiling. And do not even mention my vehicular projects!

K insisted on going small with the mindset that if there is less space, there is less cleaning. But I don’t see our household effectively reducing its contents to make that vision a reality. We would just be creating more unpleasant clutter. So I wanted to go bigger. Way bigger. After I realized what the expense of building a small ADU (Accessory Dwelling Unit, like a guest house or carriage house) would be, and also dreading the return to the humidity of the Midwest, I decided whatever we build needs to be large enough that the home would be future-proofed.

It would have the capacity to be multi-generational (when more than a single adult generation lives under the same roof). It would have the potential to house all those luxury rooms that I dreamed of (home theater, library, safe room). It would have a giant garage for those project vehicles (1969 IH Scout and 1978 Cherokee Chief). It would give K dedicated space.

Finalizing Our requirements

It could have all of these things. But initially, I thought all I’d need was a giant clear-span footprint. This concept of building a shell and finishing at our leisure ended up being a zoning ordinance pitfall I did not initially catch while researching our property (see the previous post: Land Expedition – Finding Raw Property). Without excessive meetings for a variance, I could not build an outbuilding before the primary dwelling. And if you build a primary dwelling, you have to meet all the requirements for a Certificate of Occupancy (i.e. sleeping quarters, bathroom, and kitchen).

Our plan became building an MVP, a term I have taken from software engineering (which was probably stolen from some other engineering discipline): Minimum Viable Product. We would design a home that has the capacity and potential of all the things we might want in the future, but initially, we only finish what we need for a CoO. I will delve the design iterations in my next post, but for now, our requirements were a large, clear-span building with 2 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, and enough height to build a 2nd story.

Architectural Style

Just because we were leaning towards post-frame construction, it did not necessarily mean the structure needed to look like a barn. When deciding on your outward appearance, it is important to consider the surrounding environment. You do not want to be an abhorrence in your neighborhood. Along the same line, be aware of the danger of pricing your dwelling beyond its neighborhood. If a catastrophe strikes and you need to sell, you may not get close to what you spent because the neighborhood drags down the market price.

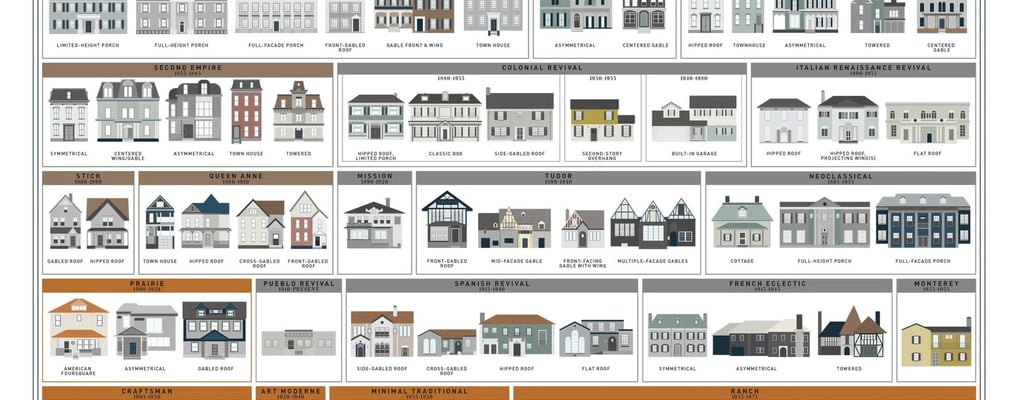

Ultimately, the architectural style is a personal, subjective choice. We ended up somewhere between a modern farmhouse and a lodge since I did all the designing. If you want to read more about American architecture, check out A Field Guide to American Houses (Revised): The Definitive Guide to Identifying and Understanding America’s Domestic Architecture by Virginia McAlester. It’s a masterwork reference for home styles packed with photos.

This wonderful chart of American architecture is from PopChart.com

Foundation Type

There are three choices here: basement, crawl space, or slab. Technically, there are more variations, but only concrete and conditioned variations are considered. Building code anywhere there is potential for snow and freezing temperatures will require frost walls, so a monolithic pour will not do well, especially for a residential building. We selected a slab foundation with a partial basement. The following is not an exhaustive list of pros and cons, but will get you started in your own research.

Basement

- Pros: Increased property value. Emergency shelter. Additional living space. Extra storage.

- Cons: The most expensive of the three options, but really, if you already need 3+ feet of frostwall, might as well form up another 6 to 8 feet, right? Most susceptible to flooding. Potential for air quality issues. Also, your particular geology might not be conducive to sinking living space that deep into the ground, and the cost of building materials up is steep.

Crawl Space

- Pros: The primary advantage of a crawl space is that all the water and waste lines are more accessible than if they were buried in concrete. They afford a better protection against flooding. Might be suitable for storage (but do yourself a favor and don’t).

- Cons: The cost will be significantly more than a slab, as you’ll be investing in the same subgrade material (insulation, vapor barriers, etc.), but with the additional cost of floor joists or trusses and maybe additional excavation. The floors will tend to creak. They are more susceptible to moisture and pests, so require more maintenance.

Slab

- Pros: Slabs have thermal mass and help regulate indoor climate. Practically impervious to pests. Does not rot like wood. Cheaper to build.

- Cons: Water and waste lines that end up buried are harder to access. Prone to severe cracking and frost heave in colder climates if not engineered and executed correctly.

Framing Method

An entire series could be written about framing methodologies. I attempt to condense the knowledge. There are two basic types of framing: heavy and light.

Light Framing

Conventional vertical stud framing with dimensional lumber, widely referred to as stick-built, is often the first thought when talking about light framing. The strength of light framing comes from its engineered sheathing, which today is mostly OSB (oriented strand board) or plywood. However, light-steel framing and SIP (structural insulated panels) also fall into this category. Structures can either be balloon (studs extend all the way to the roof) or platform framed (studs only extend to the top and bottom plates of a floor). Balloon framing is the strongest, but platform framing can be made strong and is generally easier to frame.

Heavy Framing

Heavy framing involves the use of substantial vertical post and beam structures. Studs, if any, run horizontally. Popular variations include post-framing (pole barns), timber framing (using traditional wood joinery like mortise and tenon), post & beam (timber frame, but with metal fasteners and less labor), or heavy-steel framing as seen in PEMBs. Heavy framing lends itself to large spans clear of interior load-bearing walls, which is what we selected for the Hoosier Homestead.